On Thursday, I released my newest research for the CIS, titled Learning Lessons: The future of small-group tutoring. Because small-group tutoring has become such a popular policy option in recent years, I wanted to dig deeper: what can we learn from literature and the COVID experience about small-group tutoring in Australia, and what should happen next? What follows is a more conversational summary of my paper, with some additional threads of what’s happening elsewhere in Australian education.

Small-group tutoring is intended to fix a real issue.

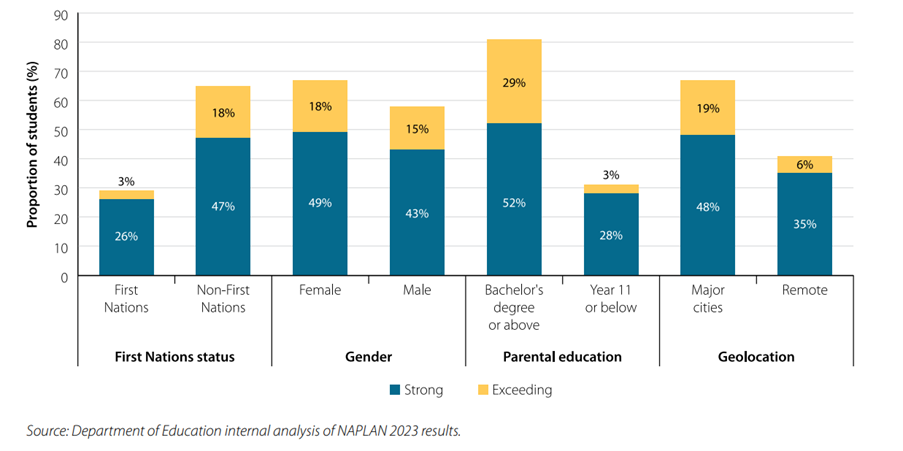

The national results for NAPLAN 2024 are yet to be published, but NAPLAN 2023 - the first year with a new scale score system and to report achievement in four bands - showed this clearly. Roughly a third of students across all year levels and domains did not meet proficiency, which is defined by ACARA as meeting Strong. In contrast to the old national minimum standard, this gives parents and the public a clearer view of where students aren’t making as much learning progress as they should be.

Moreover, once kids fall behind, they’re not likely to catch up. AERO analysis of students who were at or below the minimum standard in Year 3 reading and numeracy shows roughly a third (37.4% for reading, 33.6% for numeracy) were consistently at this level all the way through to Year 9. Clearly, current practices used by schools are not sufficient at consistently helping students to keep up, or catch up if they do fall behind.

You can’t intervene your way out of a Tier 1 problem

The trouble with reaching for small-group tutoring, or any form of small-group intervention, as the solution to this problem is that by any metric - whether it’s funding, teacher supply, capacity in school timetables - a third of all students is too large a proportion for any school to make it work.

Remember, too, a third represents a national average. The Review to Inform a Better and Fairer Education System, which is intended to form the next funding agreement between Australian governments, recommended small-group tutoring within a multi-tiered systems of support. As I’ll get to, MTSS is the only way to go - but you can’t skip over the Tier 1 part. That report also showed the way (under)achievement is overrepresented in certain student groups.

Proportion of students meeting proficiency for Year 9 Reading by First Nations status, gender, parental education, and geolocation 2023.

You would have to have half a year level (two-thirds in remote schools), in intervention. How would you even get the staff in a time of staff shortages? Schools know this is not realistic.

When governments funded tutoring, it cost a lot - but didn’t benefit students.

We tried tutoring at scale in NSW (2021-23) and Victoria (2020-25) during and after COVID. Schools were ultimately able to implement it however it suited them, and students in the program made no more progress than their peers.

I discuss the findings of the NSW evaluations and Victoria’s Auditor-General (VAGO) report in detail in the paper. I did a tweet thread on the VAGO report - which only came out last month, or you can read stories in The Age here (about the secret, rejected-in-FOI-requests Deloitte report which was used to extend the tutoring program for the 2024 and 2025 school years) and here, about the VAGO report.

When we gave schools complete control - and little in the way of guardrails and guidance - the decisions they made, despite best intentions, didn’t benefit students. What’s needed is the systematic approach of response to intervention (RTI)/multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS), but schools lack capacity to implement MTSS with fidelity, and policymakers haven't given them the tools to do it properly.

This is just Victoria, but this is what their Department of Education provides as example case studies for providing assistance to students with literacy and numeracy difficulties:

Getting MTSS right

Even if we adopt the language of MTSS, that’s not enough - Victoria has used this language for some years, but it still coincides with highly flawed guidance such as the above.

Instead, policymakers need to take concrete actions to embed MTSS capacity across Australian education. My recommendations focus on each part of the enabling factors for MTSS success, as well as how to make these systems work at scale.

Whole class instruction

The good news is, we are making some progress on whole-class instruction, with shifts in critical areas of pedagogy, curriculum, and curriculum resourcing.

Pedagogy

The NSW Department of Education, particularly under its current head, Murat Dizdar, has committed to explicit instruction. Victoria’s Education Minister, Ben Carroll, followed suit last month and backed it up on day one with a new Victorian Teaching and Learning Model, which looks like it draws heavily on AERO work. (Maybe he read this Substack post of mine which excoriated the old VTLM?)

Here’s Minister Carroll holding a very familiar report at The Age Schools Summit in June as he made his announcement. (Photo credit: The Age)

Definitions around explicit instruction seem to be getting tighter, which is much needed. But another question is, explicit instruction of what? A curriculum or syllabus oriented towards skills and intended for autonomous, school-based implementation will be difficult for schools to use EDI frameworks with.

Curriculum

So it’s good news that, following the stated shift in pedagogy, NSW is moving on curriculum as well. The NSW Education Standards Authority this week launched its new syllabus, which adapts the Australian Curriculum with more careful sequencing and detail, due for implementation from 2027. These changes - which you can read more about here - are welcome. Hint hint, Victoria.

But curriculum’s only part of the story. As Jordana Hunter and Nick Parkinson have written today, written curriculum and enacted curriculum are different things - teachers will need support with the latter. Curriculum change (or any policy decision for that matter) can only benefit students if it directly impacts teachers’ classroom practice.

Resourcing

My own research supports the notion that if we want science of learning-informed approaches in schools (explicit instruction of a knowledge-focused curriculum), putting the work back on to teachers to change their pedagogical approach AND their teaching and learning programs makes it too hard. As I wrote in February in Implementing the science of learning: teacher perspectives:

One of the most common barriers to implementation was practical: even if schools have identified the need, understand the learning science and know what practical changes need to be made to instruction, the resources need to come from somewhere. A common response from our research participants was the desire to see the Department of Education do more to support schools in the area of curriculum resourcing.

Both NSW and Victorian governments are moving on resourcing (although, in Victoria’s case, the move on resourcing predated the pedagogy shift, and is happening without any update to the Victorian Curriculum… time will tell how valuable the final products are).

In the interim, state governments should direct schools to Ochre Education. They are already doing smashing work by creating quality materials to operationalise the curriculum. Their new partnership with the Paul Ramsay Foundation announced this week will work with disadvantaged schools to implement those resources, schools which often face additional barriers to creating and using high-quality instructional materials.

Screening and assessment

On screening and diagnostics, we have ad hoc practices. The Year 1 Phonics Check is the most widely adopted screening tool, as it is mandatory in most states. Recently, my colleague Kelly Norris has made some hugely impactful work advocating a Year 1 screener for maths. Her report forms the basis for future CIS work in developing and trialling exactly such a screener.

There are some green shoots here too. NSW Education Minister, Prue Car, spoke to The Australian [$] to back a nationally consistent numeracy screening check:

Ms Car called for children to be tested on their mathematical knowledge at the start of primary school, along with the “phonics check’’ that was opposed nationally by teacher unions.

“Why don’t we talk about nationally doing a numeracy check for our kids in Year 1, once they can properly read, to be able to assess where they are at with basic numeracy,’’ she told The Australian. “Taxpayer funding in education should be tied to making sure that we are doing the very best for our kids.’’

But one nationally consistent screening point in one year level isn’t enough to meet requirements for successful MTSS, which requires regular universal screening. And screening tools aren’t diagnostic assessments, which are also needed for adequately targeting intervention.

Secondary: a whole different ballgame

MTSS interventions in secondary schools are also different to primary - it seems harder to generate impact. AERO is steadily publishing work in this space, which includes some profiles of secondary schools across the country who are taking some promising steps.

Another school I would add to the list is Rosebud Secondary College - their principal Lisa Holt and two of her colleagues presented at Sharing Best Practice Gippsland about their work. Ms Holt pointed out in that presentation that although the school has received media attention for its shift in behaviour, the school sees improving student behaviour and improving student academic outcomes as mutually reinforcing.

In addition, Jessica Colleu Terradas - who blew me away at a ResearchEd in 2019 talking about the benefits of Corrective Reading at her then-school, Como Secondary Colleague - and my fellow Teach for Australia alum, Melanie Henry, are currently undertaking PhDs to add to the knowledge about literacy intervention in secondary schools. Jess is also convening the Literacy Intervention in Secondary Schools network.

Shining a light on success

What struck me from the evaluations of the tutoring program - and something the Vic Auditor-General observed - is that schools could actually generate great outcomes from tutoring. But there wasn't enough attention paid (at least in the published evaluations) looking 'under the hood' at successful practices. Certainly, as the Auditor-General concluded, the Victorian government didn’t do enough to use early rounds of data to refine/improve their guidance to schools.

But those schools must still exist. My hunch is that Docklands Primary probably got good mileage out of their tutoring funding because they have a systematic approach. Check out this video here:

Docklands Learning Specialist Brad Nguyen wanted his followers to watch the video and observe:

1. Students in rows

2. Mini whiteboards

3. PRIME Maths textbooks

4. Document camera

5. Ochre daily review slides

6. Interactive whiteboard

7. Students using place value discs

8. Rocket Math intervention

9. Connecting Math Concepts intervention

This is the kind of nitty-gritty schools need to know (Which screeners and assessments? Cut scores? Intervention programs? Decision trees?), but whether they have that knowledge is just a matter of chance.

The key takeaways

The instinct to help kids catch up is good. Too many kids are slipping through the cracks at early year levels and turning into casualties of poor instruction.

But we can’t rely on small group methods. Better universal practices needed to ensure proper allocation of resources to students in Tier 2 and above. This includes screening and assessment.

Schools aren’t equipped to make all these critical decisions alone and too many are left to ‘magpie’, especially in critical areas like screening and diagnostic assessment where there’s not much on the Australian market that fits the bill.

Policymakers need to invest in knowledge dissemination - not just in screening, but also in the selection of intervention programs and progress monitoring tools - to enable better decision-making.

Some schools will already have excellent MTSS systems. Go and find them. Find out what they do, and help them to help other schools.

Governments should be commissioning AERO or other entities to do some of the work I’ve recommended. In the meantime, governments should not be striking a funding deal which embeds SGT/MTSS when the enabling factors are so unevenly divided across Australian schools.

Further reading

‘Luck of the draw’: why small-group tutoring programs should not be scaled out - in Education HQ

Tutoring programs having little bang for buck, study shows - in The Educator Online